Uncategorized

Understanding Python module usage on GitHub with python-api-inspect

Sunday, July 14th, 2019 | Uncategorized | No Comments

A SciPy 2019 lightning talk by Chris Ostrouchov introduced me to his project python-api-inspect. This provides an API for querying Python package usage on GitHub (and hopefully soon other source control systems).

It includes very flexible SQL queries, for example this one which we used to find packages that use the sympy.physics.quantum package within sympy:

If you click on the link you can fill in your own project and package to search for.

The Scientific Method

Saturday, July 13th, 2019 | Uncategorized | No Comments

A lightning talk I gave at SciPy 2019 in Austin, Texas,

A common view of the scientific method is that it consists of:

- formulating a hypothesis, and then

- conducting experiments to falsify or confirm this hypothesis.

This view has a few problems:

- It suggests a black and white picture where hypotheses are either right or wrong.

- It paints a picture of science as a large body of disconnected statements.

- It presents a narrow view of science where experiments are of primary importance, and

- I don’t think it matches how science actually happens.

These problems are far from academic. Science encounters a significant amount of skepticism & societal views are often polarized. I don’t think the common view of the scientific method is helping. When people are bombarded with many short disconnected statements and not given any tools to connect or reason about these themselves, it’s not surprising that many of them become confused.

I think a more useful view of the scientific method is as building and characterizing models

Let’s take vaccines as an example. I’m fairly sure that the measles vaccine doesn’t cause autism, and if someone came to me with evidence that it did, I’d be fairly skeptical. This isn’t because I’ve done a lot of experiments of my own though, or read a lot of papers by experimenters I trust. It’s because I have a simple model in my head of what the measles vaccine is — an attenuated form of the measles virus. Thus it seems unlikely that the vaccine would do something the virus didn’t. On the other hand The Cutter Incident in the 1950s where Cutter Laboratories distributed vaccines accidentally containing live polio virus seems very plausible in terms of the model.

If we’re going to win over science skeptics, we’re going to have to explain our models. This is a harder kind of educating than stating facts & hoping to be believed & hoping that we were right in the first place — but no one said this was going to be easy.

Science is about model characterization. We build mental models and characterize them. We expand their consequences. We understand when they’re valid and when they’re not and how accurate they are. We simplify and improve them.

Models come in many shapes and sizes. They might be as simple as a drawing, or as complex as the standard model of quantum mechanics.

Experiments still have a unique value — their measurements are independent of our models. But how we decide which experiments to do and how we interpret the results is very model dependent.

As an added bonus, this model-based view looks Bayesian and solves the “all ravens are black” paradox.

But more importantly, a common set of models allows us to have a conversation — even if we disagree about the details. They allow us to come to shared conclusions and have constructive disagreements — to have a shared mindset. Models that are well characterized can be depended upon in their domain of validity. They allow us to have the “what if …” conversations that are the

basis of policy.

For many important issues we can’t perform experiments. We only have one planet and one life to live.

Where to from here?

Saturday, October 3rd, 2015 | Uncategorized | No Comments

Closing speech at the end of PyConZA 2015.

We’ve reached the end of another PyConZA and I’ve found myself wondering: Where to from here? Conferences generate good idea, but it’s so easy for daily life to intrude and for ideas to fade and eventually be lost.

We’ve heard about many good things and many bad things during the conference. I’m going to focus on the bad for a moment.

We’ve heard about imposter syndrome, about a need for more diversity, about Django’s flaws as a web framework, about Python’s lack of good concurrency solutions when data needs to be shared, about how much civic information is locked up in scanned PDFs, about how many scientists need to be taught coding, about the difficulty of importing CSV files, about cars being stolen in Johannesburg.

The world is full of things that need fixing.

Do we care enough to fix them?

Ten years ago I’d never coded Python professionally. I’d never been to a Python software conference, or even a user group meeting.

But, I got a bit lucky and took a job at which there were a few pretty good Python developers and some time to spend learning things.

I worked through the Python tutorial. All of it. Then a few years later I worked through all of it again. I read the Python Quick Reference. All of it. It wasn’t that quick.

I started work on a personal Python project. With a friend. I’m still working on it. At first it just read text files

into a database. Slowly, it grew a UI. And then DSLs and programmatically generated SQL queries with tens of joins. Then a tiny HTML rendering engine. It’s not finished. We haven’t even released version 1.0. I’m quietly proud of it.

I wrote some games. With friends. The first one was terrible. We knew nothing. But it was about chickens. The second was better. For the third we bit off more than we could chew. The fourth was pretty awesome. The fifth wasn’t too bad.

I changed jobs. I re-learned Java. I changed again and learned Javascript. I thought I was smart enough to handle

threading and tons of mutable state. I was wrong. I learned Twisted. I couldn’t figure out what deferreds did. I wrote my own deferred class. Then I threw it away.

I asked the PSF for money to port a library to Python 3. They said yes. The money was enough to pay for pizza. But it was exciting anyway.

We ported another library to Python 3. This one was harder. We fixed bugs in Python. That was hard too. Our patches were accepted. Slowly. Very slowly. In one case, it took three years.

Someone suggested I run PyConZA. I had no idea how little I knew about running conferences, so I said yes. I asked the PSF for permission. They didn’t know how little I knew either, so they said yes too. Luckily, I got guidance and support from people who did. None of them were developers. Somehow, it worked. I suspect mostly because everyone was so excited.

We got amazing international speakers, but the best talk was by a local developer who wasn’t convinced his talk would interest anyone.

I ran PyConZA three more times, because I wasn’t sure how to hand it over to others and I didn’t want it to not happen.

This is my Python journey so far.

All of you are at different places in your own journeys, and if I were to share some advice from mine, it might go as follows:

- Find people you can learn from

- … and make time to learn yourself

- Take the time to master the basics

- … so few people do

- Start a project

- … with a friend(s)

- Keep learning new things

- … even if they’re not Python

- Failure is not going to go away

- … keep building things anyway

- Don’t be scared to ask for money

- … or for support

- … even from people who aren’t developers

- Sometimes amazing things come from one clueless person saying, “How hard can it be?”

- Often success relies mostly on how excited other people are

- Stuff doesn’t stop being hard

- … so you’re going to have to care

- … although what you care about might surprise you.

Who can say where in this complicated journey I changed from novice, to apprentice, to developer, to senior

developer? Up close, it’s just a blur of coding and relationships. Of building and learning, and of success and

failure.

We are all unique imposters on our separate journeys — our paths not directly comparable — and often wisdom seems largely about shutting up when one doesn’t know the answer.

If all of the broken things are going to get fixed — from diversity to removing the GIL — it’s us that will have to fix them, and it seems unlikely that anyone is going to give us permission or declare us worthy.

Go build something.

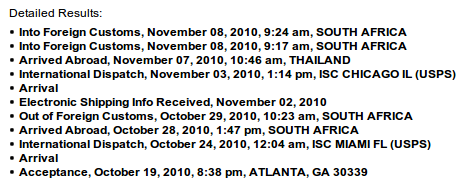

Using a Telkom Huawei modem under Ubuntu

Sunday, July 8th, 2012 | Uncategorized | No Comments

Telkom sell a wireless land-line phone build on the Huawei ETS6630 chipset. Under the hood it’s essentially a cellphone in a land-line form factor and it has a USB connector on the side that allows it to function as a USB GSM modem. However, there are a couple of obstacles to getting it running under Linux (specifically Precise):

- When first plugged into a USB port, it’s just a USB storage device (containing the Windows drivers). It needs to be sent a special command to make its GSM modem available.

- There is a utility for doing this (usb_modeswitch) but the version in Precise doesn’t pick up Telkom’s phone by default.

To help usb_modeswitch along, create /etc/usb_modeswitch.d/12d1:1011 containing the configuration needed for the Telkom phone:

# /etc/usb_modeswitch.d/12d1:1011 # Huawei ETS6630 TargetClass=0xff HuaweiMode=1

The “12d1″ and “1011” are the vendor and product code that identify the device. The TargetClass tells usb_modeswitch how to recognize when the GSM modem has been activated. HuaweiMode specifies the command to send to activate the device.

Then edit /lib/udev/rules.d/40-usb_modeswitch.rules to add:

# /lib/udev/rules.d/40-usb_modeswitch.rules

# Huawei ETS6630

ATTRS{idVendor}=="12d1", ATTRS{idProduct}=="1011", RUN+="usb_modeswitch '%b/%k'"

This tells udev to call usb_modeswitch when the Telkom phone is connected. Unfortunately these rules can’t just be put into /etc/udev/rules.d/ because 40-usb_modeswitch.rules includes additional actions needed to help recognize the device as a GSM modem.

If everything is working, you should now be able to restart NetworkManager and add a new Mobile Broadband connection via NetworkManager’s GUI. If things go wrong you can watch what is happening by tailing /var/log/syslog and watching what happens when you plug the Telkom phone into the USB port. Using “lsusb” and “lsusb -v” to look at what interfaces the Telkom phone is currently providing and poking the phone directly with “usb_modeswitch -v 12d1 -p 1011 -H” can also help. Note that running “usb_modeswitch” from the command-line won’t be enough to get the phone picked up as a USB serial device (that’s what all the additional rules in 40-usb_modeswitch.rules are for).

Hopefully I can get these fed back to the maintainer of the usb-modeswitch-data package and this blog post will become irrelevant. :)

Addendum: You might need to `modprobe options` and `modprobe usbserial` to get this to work (it looks like usb_modeswitch is meant to do this but my hacky additions don’t appear to get those steps to happen).

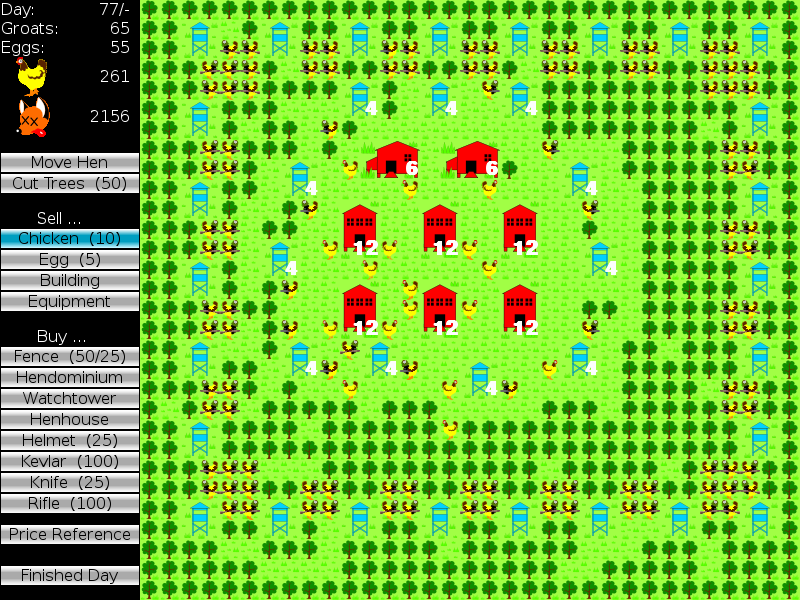

The Rinkhals has Eclectic Tastes (PyWeek 9)

Monday, September 7th, 2009 | Uncategorized | No Comments

This past week Confluence, Jerith, Nitwit, David and I took part in PyWeek 9 — an online challenge to write a computer game in one week. The result is Operation Fox Assault. It’s a bit like what Warcraft would have been if the protagonists were chickens and the game had been written in a week. Mac, Windows and Linux downloads are available on our team page.

Now for some general musings on the PyWeek that was.

Each PyWeek begins with the entrants voting on a theme. The result is announced at midnight (GMT) on a Saturday and this is the starting gun for the one week of development. Final submissions must be uploaded before midnight the following Saturday, although there is a twenty-four hour grace period after that to allow developers to fix critical bugs or sort out problems with packaging and uploading their entries.

This PyWeek’s theme was ‘Feather’. The Sunday morning after the announcement the core Rinkhals team gathered at the Yola offices to brainstorm game ideas and strategise. I think it was Jerith that came up with the spark that resulted in the Operation Fox Assault concept but even before the idea was fully formed the entire team was running with it. A few whiteboard sketches later and we were stuck in to game development. Initially Confluence was doing artwork, Jerith was creating the tile map and Nitwit and I were running around putting general architecture such as the game engine in place.

Based on discussions overheard on th #pyweek channel it seems we were one of the few teams to get off to a rapid start. Many of those represented on the channel were still hunting around for basic game concepts on the second day of the competition.

Looking back at that first session there were two things that were to aid us greatly in the week ahead:

- We had a good concept that the entire team was enthusiastic about.

- We were realistic about what was achievable. Nitwit pointed out that we each had about twenty hours of development time available and although we did extend that a bit by working long evenings during the week, I think it was a solid estimate of the subjective time available.

At the end of the first day we had something that ran and displayed the game board.

The rest of the week was a frenzy of development (except for Tuesday evening which was spent playing V:tES). On Wednesday Jerith came round to our place to code. Sometime in the middle of the week David joined the team and added sound. Stubbed code written by one developer was suddenly leapt on by other developers and turned into fully fledged features.

From a programming perspective the tight deadline was surprisingly liberating. Gone was agonizing over how best to structure code or long-term maintainability. Grabbing low-hanging fruit and rapid development were the order of the day.

Team Rinkhals is almost certainly the most talented development team I’ve had the privilege to be part of and I have a newfound appreciation for what a difference a talented team makes. Not once did I have to explain basic Python or programming concepts, or show someone how to use svn merge or dive into the internals of a library to debug something for someone else. I felt I could trust the code committed by my fellow team members — which given that there was very little time to read it was helpful.

By the time the final Saturday arrived we were in pretty good spirits. Operation Fox Assault was in good shape and although there were a reasonable number of items left on the to-do list most of them were minor enhancements and polishing. The big outstanding items were packaging the game for Windows (using py2exe) and Mac (using py2app). I got stuck into the py2exe work in the early evening. There were some scary moments when the py2exe build was segfaulting but eventually at around ten o’clock the Windows packaging was sorted out and we headed out to Roxy’s for a leisurely dinner. We returned shortly before midnight. Jerith put the finishing touches on the py2app packaging and the rest of us cleaned up minor bugs before submitting our entry a few minutes after 2:00am.

Now all that’s left is to take part in the judging which runs until the end of this week. I’m anxious to see Fox Assault do well, but I’m already satisfied that we ended up with a pretty cool little game — the three hours I spent playing it in unlimited mode last night are testament to this.

If you’re wondering about the rinkhals’ tastes, see the Wikipedia entry.

P.S. Also see Nitwit’s post about our team’s PyWeek experiences.